Load balancers are nowadays an essential element due to the increase of online services and the consequent need to guarantee their performance, availability and reliability. Distributed systems, exponential growth of data, dynamic microservice architectures and edge computing are just a few examples of how this element is a fundamental part of the infrastructure in an increasingly delocalized and distributed world. Without going into too much depth I will review in the below sections some main features and concepts related to this type of devices.

Load Balancers vs. Reverse Proxies

Although both types of components sit between clients and servers in a client-server computing architecture, accepting requests from the former and delivering responses from the latter, they may present subtle differences and particular use cases. Let’s see it.

Load Balancers

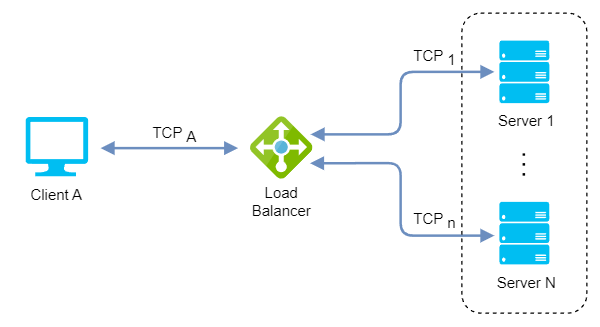

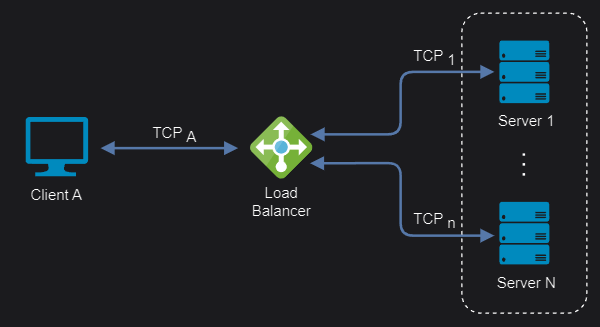

A load balancer focuses on routing incoming client traffic to the appropriate backend pool (two or more backend servers supporting the same service) distributing traffic equally across the servers in that pool.

Particular functionalities related to a load balancing device are:

- Traffic routing: Forwarding of client requests to the appropriate backend pool based on specific rules.

- Load balancing: Distributing of client requests to the best backend server in the pool based on specific algorithms.

- Service discovery: Detecting and identifying available backend servers on a network automatically.

- Session persistence: Maintaining the state of a user’s session across multiple requests by ensuring that all requests from the same user are sent to the same server (also known as session stickiness or affinity).

- Health checking: Polling your backend servers by attempting to connect at a defined interval (also known as active health check).

- Circuit breaker: Monitoring live traffic for errors and determining the health of targets (also known as passive health check).

It is important to differentiate the terms routing and balancing and not to use them interchangeably. Keep in mind that load balancing implies routing requests, but the opposite is not necessarily true. Traffic routing makes a decision on where to forward requests and load balancing distributes those requests among a set of resources designed to process them.

And so, benefits resulting from the above functionalities are:

- Performance: Distributing traffic between backend servers leads to improve response times.

- Availability: Detecting and redirecting traffic away from failed backend servers.

- Scalability: Allowing for seamless horizontal scaling (scaling-out) of backend servers.

- Security: Reducing the attack surface by hiding backend servers reduces external threats.

Reverse Proxies

Instead, a reverse proxy focuses on just routing incoming client traffic to the appropriate backend server, even with just one server supporting a single service (typically a web server).

Please note that the core function of a reverse proxy is to accept requests and forward them to servers, no additional logic or function is strictly necessary behind it. However, reverse proxies typically embes a wide range of capabilities, where load balancing is just one of them.

Accordingly, reverse proxies are able to offer the supposed load balancer functionalities as well as the following:

- Request/response transformation: Rewriting URLs to adapt to the backend server’s requirements, adding or removing headers, modifying cookies or even the content of the body.

- Caching: Storing static and dynamic content to improve response times for subsequent requests.

- Compression: Encoding, restructuring or otherwise modifying data in order to reduce the size of transmitted data and improve delivery speed.

- SSL/TLS termination: Providing a single point of configuration and management, and offloading the process of encrypting/decrypting traffic away from web servers.

- Web application firewall (WAF): Inspecting and filtering incoming requests protects backend servers from direct exposure to the Internet.

- Centralized logging: Intercepting client requests directed to your backend servers and logging them before forwarding.

For all the above, additional benefits to those of the load balancer are:

- Flexibility: Unifying several domains and subdomains under the same IP address and identifying which backend system should handle the request.

- Maintainability: Abstracting clients from the backend servers make it easier maintenance and upgrades (like deactivating a server or replacing software/hardware).

- Performance: Caching, compression and SSL/TLS offload improves web acceleration reducing the time taken to generate a response and return it to the client.

- Security: Inspecting and filtering client traffic protects the backend servers from DDoS attacks, SQL injection, cross-site scripting and other malicious behaviors.

- Observability: Because all client requests are routed through the reverse proxy, it makes an excellent point for logging and auditing.

Are load balancers and reverse proxies therefore the same? The short answer is no. While load balancers are a particular case of reverse proxies, not all reverse proxies necessarily perform as load balancers. However, as they primarily do, it leads to the terms load balancer and reverse proxy being considered equivalent. Some popular open-source software proxy solutions with load balancing capabilities are Apache (mod_proxy_balancer), Nginx, HAProxy and Envoy, for example.

Layer 4 vs. Layer 7 Load Balancers

In order to make these distinctions it is important to keep the OSI model in mind. Take it with caution, as the OSI model is just a theoretical framework intended to provide guidance rather than a one-size-fits-all explanation, unfortunately. However, an extremely simplified one will do the job:

| Layer | Function | PDU | Example | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 | Application | Human-computer interaction | Message | HTTP |

| 6 | Presentation | Syntax, compression and encryption | Message | SSL/TLS |

| 5 | Session | Logical communication control | Message | RPC |

| 4 | Transport | Process-to-process communication (port numbers - 0 to 65535) |

Segment Datagram |

TCP UDP |

| 3 | Network | Host-to-host wide delivery (logical addresses - IPs) |

Packet | IP |

| 2 | Data link | Node-to-node local delivery (physical addresses - MACs) |

Frame | ARP |

| 1 | Physical | Bit-by-bit medium delivery (wire, fiber, wireless) |

Bit | Ethernet IEEE 802.3 WiFi IEEE 802.11 |

It is important to note that a load balancer labeled with a layer level would be able to provide the capabilities of that layer level and below. Thus, a layer 7 load balancer could also perform layer 4 functions and so on.

Although technically layer 2 load balancers exist, they are very specialized scenarios. Thus, we are focusing on studying the aspects of layer 4/7 load balancers, specifically related to TCP/HTTP protocols (since HTTP uses TCP as transport protocol).

Layer 4

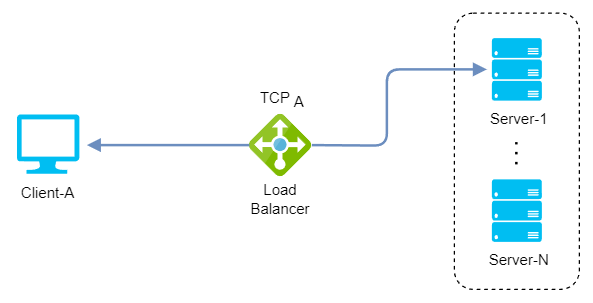

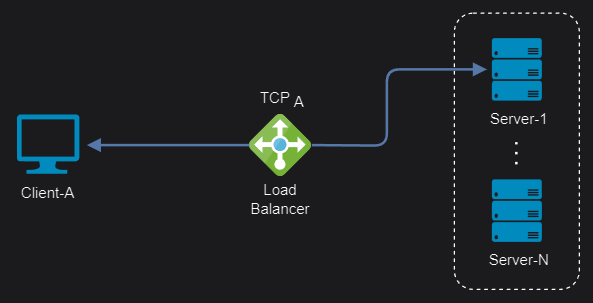

Layer 4 load balancers perform at the transport layer and practically make routing decisions based on the IP address (layer 3) and port number (layer 4) found in the packet header. It doesn’t inspect the application data, making it faster and ideal for TCP and UDP traffic.

Advantages:

- Fast performance: There is no data lookup, it just forwards the opaque network packets to and from the server based on the ports and the IP addresses.

- Small attack surface: Since there is no data lookup, the content of the packets can’t be compromised.

- Maximized TCP-connections: The concurrent TCP connections number is maximized by maintaining only one NATed connection between client and backend server (max concurrent connections = number of backend servers * max connections per backend server).

- App-protocol agnostic: Operating at the transport layer deals with the movement of data between devices without knowledge of the content of messages from upper layers.

Disadvantages:

- Simple load-balancing: They cannot differentiate between different types of content or apply specific routing rules based on application data.

- Sticky connections: All packets are routed to a single server in the backend until the next connection, when a server will be again selected based on the algorithm (multiplexing/keep-alive protocols are an issue here).

- Limited persistence options: Source IP Address is the only persistence option when shared data or session state is stored locally on the backend server.

- Uncached content: Because they do not examine the content of the packets being transmitted, they cannot perform caching.

- Non-Microservice oriented: Stickiness and simple load-balancing make them less effective for microservices inter-process communication based on REST API.

Multiplexing and keep-alive techniques are crucial in optimizing network communications, but they are different concepts. While multiplexing allows multiple service requests to be segmented over a single connection, keep-alive ensures that the connection between devices remains open even when there’s no data being transmitted, thus reducing the overhead of establishing new connections.

There are also layer 4 reverse proxy load balancers that are able to terminate at the load balancing layer and then distribute TCP traffic to backends (with or without SSL), although for HTTP/S traffic is recommended using a layer 7 load balancers instead.

Layer 7

Layer 7 load balancers perform at the application layer and make routing decisions based primarily on application-level messages (layers 7-5), such as HTTP headers, cookies, and URLs. This enables more content-based routing and advanced load balancing algorithms.

Remember we are focusing on HTTP but decisions could be made based on data from any other application protocol as long as it is supported by the load balancer, such as MongoDB, MySQL or Redis (on experimental support in Istio).

Advantages:

- Smart load-balancing: Reading the message within the network traffic and making a routing decision based on the message content to which even optimisations and transformations can be applied.

- Cached content: Examining the content of the packets being transmitted allows to cache frequently accessed content, such as images or static files, reducing the load on the backend servers.

- Balanced connections: Create a TCP connection with every server for a single client connection rather than choosing a single server (works well with multiplexing/keep-alive protocols)

- Multiple persistence options: Source IP Address, HTTP Cookie or SSL Session ID are just a few persistence options when shared data or session state is stored locally on the backend server.

- Microservice-oriented: Balanced connections and smart load-balancing make them better suited for microservices inter-process communication based on REST API.

Disadvantages:

- Expensive performance: Examining the content of the packets being transmitted and handling SSL/TLS encryption and decryption are more CPU-intensive tasks requiring more computing power.

- Larger attack surface: Having the SSL certificates stored on the load balancer and being capable of examining the content of the packets being transmitted make that any application security issue may be exploitable.

- Bounded TCP-connections: Concurrent TCP connections number is limited by terminating the network traffic and then making or reusing TCP connections to the selected server (max concurrent connections = max load balancer connections - number of backend servers).

- App-protocol wise: Understanding of the application protocol is needed as they operate at the application layer, which deals with the content of each message.

Load Balancer topologies

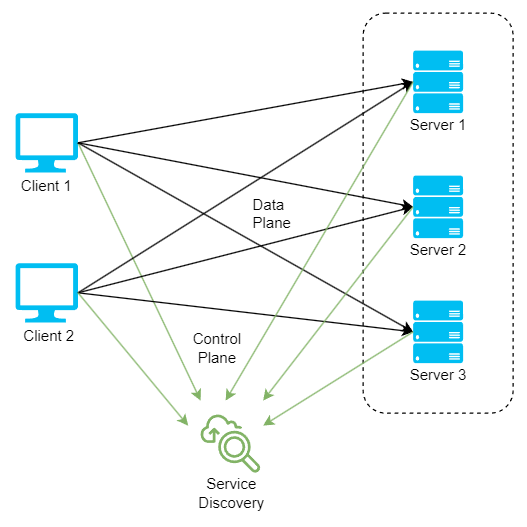

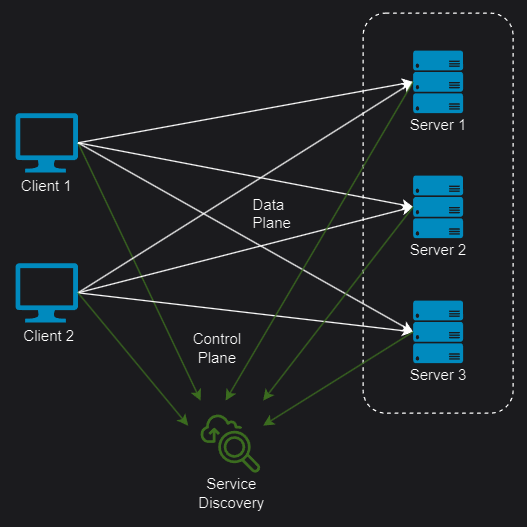

Client-side and server-side load balancing are two ways of distributing the workload among multiple servers. The main difference is where the load balancing logic is located and who makes the decision of which server to send the request to.

Server-side

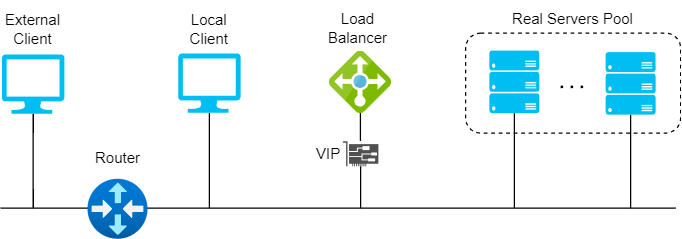

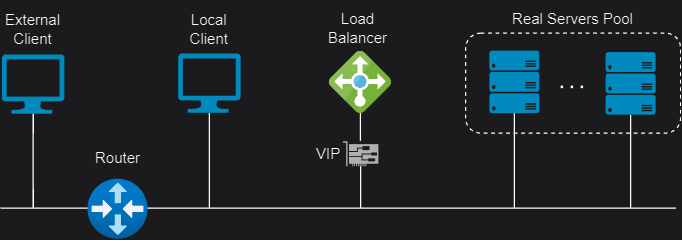

In Server-side load balancing, the instances of the service are deployed on multiple servers and then a load balancer is placed in front of them. Firstly, all the incoming requests come to the load balancer which acts as a middle component. Then it determines to which server a particular request must be directed based on some algorithm. Depending on how it is connected to the network and the servers we have:

One-Arm

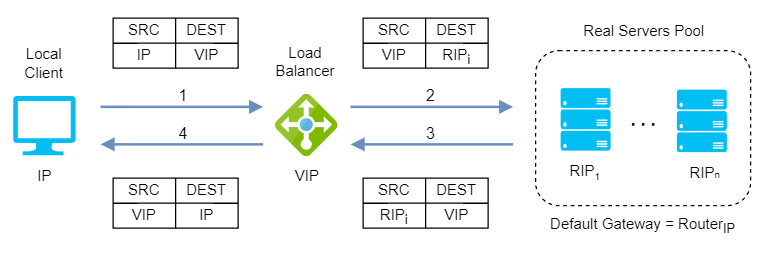

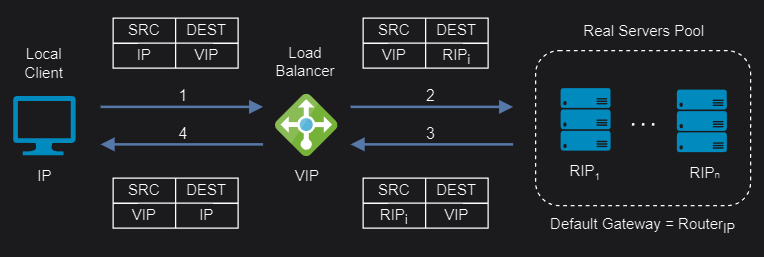

In a one-arm configuration, the load balancer is not in the traffic path between the client and the server, but rather acts as a proxy that performs source NAT/SNAT to route the traffic between them.

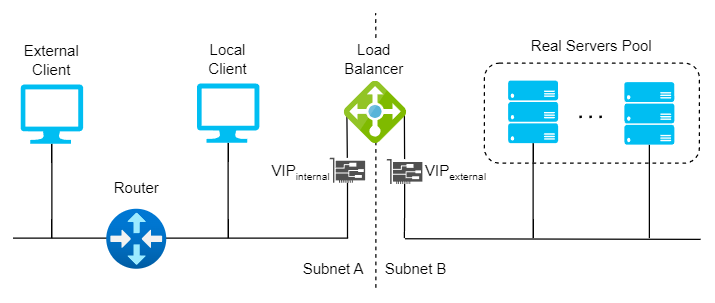

Two-Arm

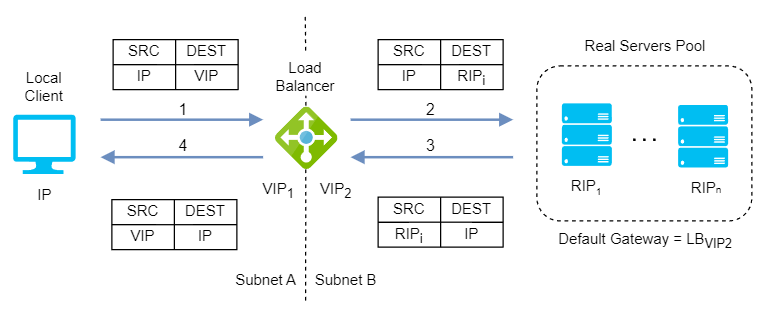

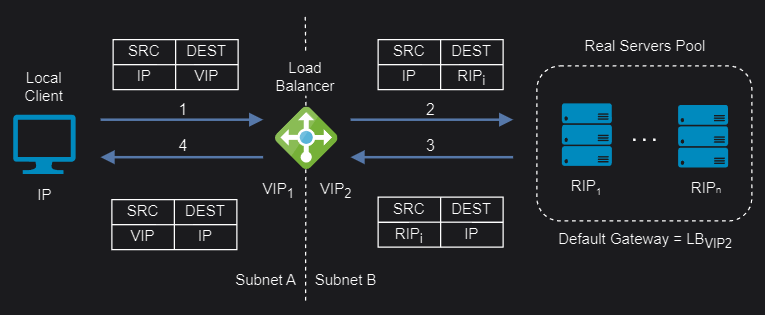

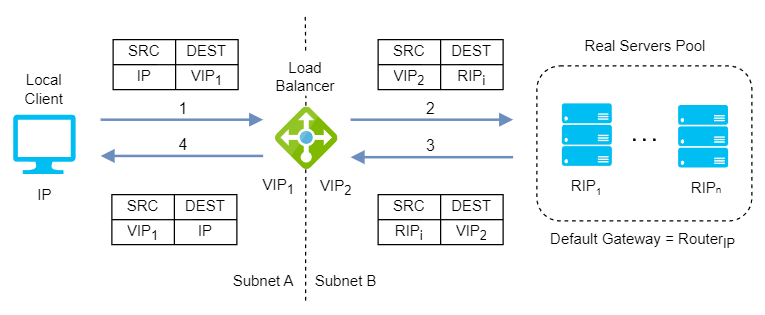

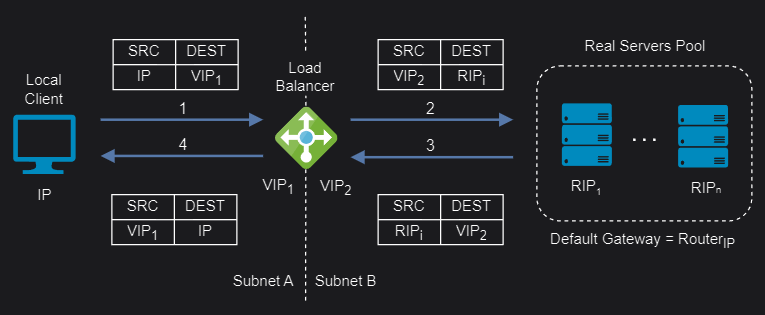

In a two-arm configuration, the load balancer has two network interfaces connected to two different subnets. In this mode, the load balancer acts as a bridge between the client and the server, and the virtual services and the servers are on different subnets.

Client-side

In client-side load balancing the instances of the microservice are deployed on several servers. The logic of Load Balancer is part of the client itself and it carries the list of servers and determines to which server a particular request must be directed based on some algorithm. Two approaches are:

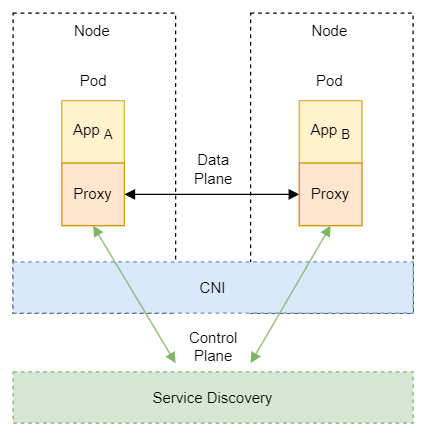

Sidecars

Sidecar load balancers are a type of load balancers that run as a separate process or container alongside each client application. They distribute the traffic between multiple servers without adding an extra network hop or a centralized bottleneck. They also provide features such as health checks, retries, circuit breaking, and metrics. Popular examples are:

-

Envoy (Istio): Istio uses an extended version of the Envoy proxy, a high-performance proxy developed in C++ to mediate all inbound and outbound traffic for all services in the service mesh. Deployed as sidecars to services, they are the only Istio component that interact with data plane traffic, improving the services with the Envoy’s built-in features.

-

Linkerd2-proxy (Linkerd): The Linkerd data plane comprises ultralight micro-proxies written in Rust and deployed as sidecar containers inside application pods. These proxies transparently intercept TCP connections to and from each pod. Unlike Envoy, it is designed specifically for the service mesh use case and is not designed as a general-purpose proxy.

Libraries

A library client side load balancer is a software component that runs on the client application and distributes the requests across multiple servers without a centralized component. It requires a service discovery mechanism to get the list of available servers and a load balancing algorithm to select the best server for each request. Popular examples are:

-

Ribbon (Netflix OSS): It is a cloud library that provides client-side load balancing for distributed applications. It is part of the Netflix Open Source Software (Netflix OSS) and it integrates with other Netflix components, such as Eureka and Hystrix. Ribbon allows users to implement their own load balancing policies or use predefined ones, such as round robin, availability filtering, weighted round robin, ring hash, and least request.

-

Spring Cloud Loadbalancer (Spring Cloud): It is a load balancer library that provides client-side load balancing for Spring Cloud applications. It supports reactive and blocking modes, service discovery integration, health checking, caching, and metrics. Spring Cloud Loadbalancer can use different load balancing algorithms, such as round robin, random, and best available.

-

gRPC Load Balancer (Google): Actually, gRPC is a RPC protocol implemented on top of HTTP/2. Client-side load balancing is a feature that allows gRPC clients to distribute load optimally across available servers. The client gets load reports from backend servers and the client implements the load balancing algorithms.

Load balancing modes

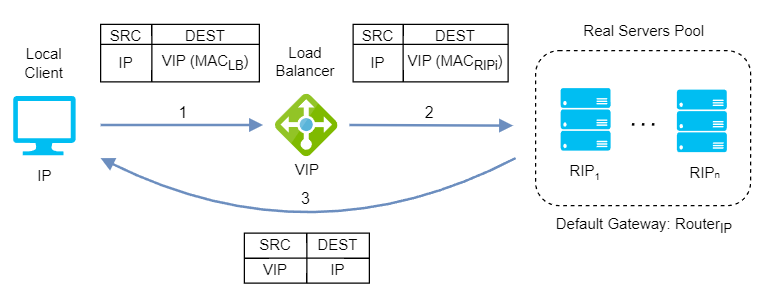

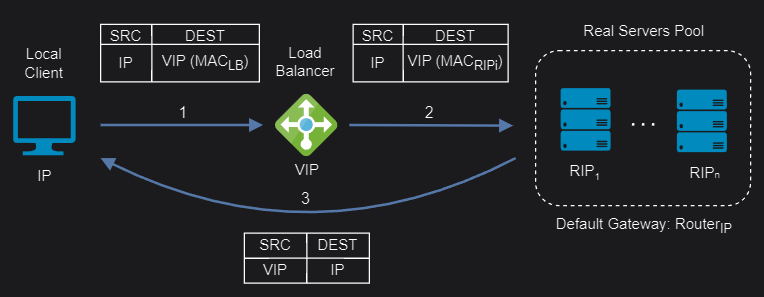

Load balancing modes can be implemented according to how load balancers handle the source and destination IP addresses of the packets that are forwarded between the clients and the servers. The most appropriate mode will depend on the specific scenario and topology, bearing in mind that multiple load balancing modes can be used at the same time or in combination with each other.

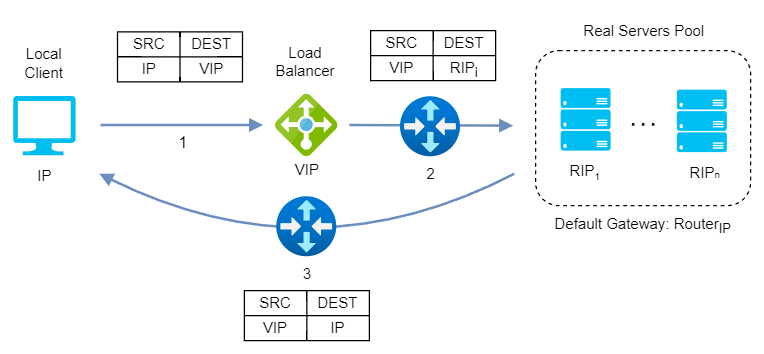

Layer 4 Direct Routing (DR)

Also known as Direct Server Return or nPath, this mode allows the backend servers to directly return the responses to the clients, without passing through the load balancer. This mode requires little change to your existing infrastructure offering high performance and scalability, as it reduces the bandwidth and processing load on the load balancer. However, it also requires some configuration changes on the servers and layer 2 connectivity, so the load balancer must be in the same subnet as the servers.

DR modes works by changing the destination MAC address of the incoming packet to match the selected server on the fly (ARP spoofing). When the packet reaches the server it expects the server to own the Virtual Services IP address (VIP). This means that you need to ensure that:

- The servers (and the load balanced application) respond to both the servers’ own IP address and the VIP.

- The servers don’t respond to ARP requests for the VIP (only the load balancer should do this).

DR mode doesn’t support port translation (for example, VIP:80 to RIP:8080) and it is transparent (the server see the source IP address of the client).

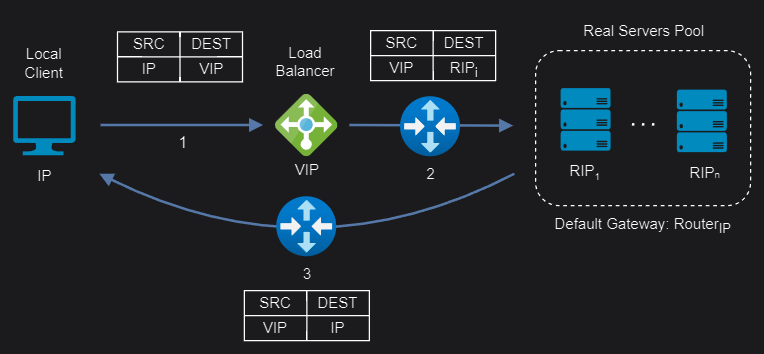

Layer 4 Tunneling (TUN)

Similar to layer 4 DR, TUN also uses direct server return but using IP tunneling to forward requests from the load balancer to the servers. This allows servers from different data centers to be used and sends the responses directly to the clients bypassing the load balancer.

TUN mode can work on any network, as long as the load balancer and the servers support IP tunneling, a technique that encapsulates an IP packet inside another IP packet, creating a tunnel between two endpoints. The load balancer uses this technique to send the original client request to the server, without modifying the source or destination IP addresses. The server extracts the original request from the tunnel, processes it, and sends the response to the client using the original source IP address as the destination.

TUN mode doesn’t support port translation and it depends on how the load balancer and the servers are set up for tranparency.

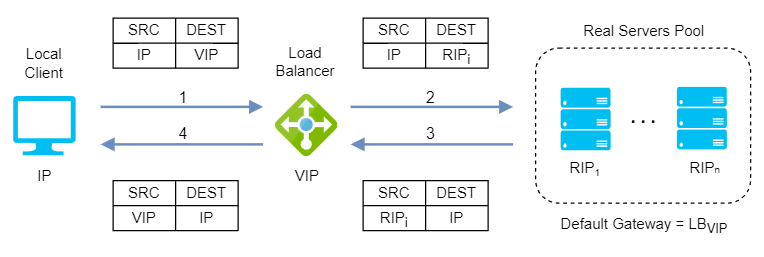

Layer 4 Network Address Translation (NAT)

Layer 4 NAT mode is also a high performance solution, although not as fast as layer 4 DR mode because server responses must flow back to the client via the load balancer rather than directly. The load balancer translates all requests from the Virtual Service to the servers. NAT mode can be deployed in the following ways:

One-Arm: The VIP is brought up in the same subnet as the servers. To support remote clients, the default gateway on the servers must be an IP address on the load balancer and routing on the load balancer must be configured so that return traffic is routed back via the router. To support local clients, return traffic would normally be sent directly to the client bypassing the load balancer which would break NAT mode. To address this, the routing table on the servers must be modified to force return traffic to go via the load balancer.

Two-Arm: The VIP is located in one subnet and the servers are located in the other. This can be achieved by using two network adapters, or by creating VLANs on a single adapter. The default gateway on the servers must be set to be an IP address on the load balancer. Clients can be located in the same subnet as the VIP or any remote subnet provided they can route to the VIP.

If you want servers to be accessible on their own IP address for non-load balanced services (for example, SSH) you will need to setup individual SNAT and DNAT firewall script rules for each server or add additional VIPs for this.

NAT mode support port translation and it is also transparent.

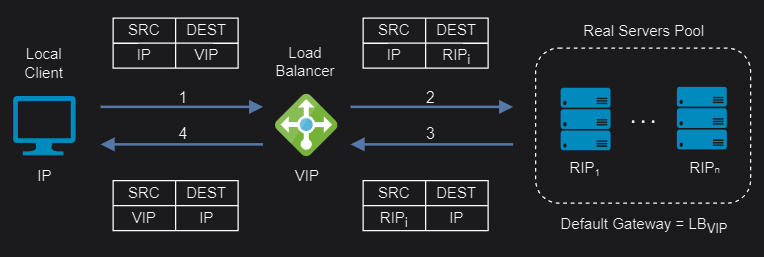

Layer 4/7 Source Network Address Translation (SNAT)

Layer 4 SNAT mode is also a high-performance solution, although not as fast as layer 4 NAT mode or layer 4 DR mode. The load balancer translates all requests in the same way as NAT mode but an iptables SNAT rule translates the source IP address to be the load balancer rather than the original client IP address.

When it comes to layer 7 SNAT mode, it becomes as a full proxy at the application layer, so any server in the cluster can be on any accessible subnet including across the Internet or WAN. Inbound requests are terminated on the load balancer and the proxy generates a new corresponding request to the chosen server, resulting not as fast as the Layer 4 modes.

Layer 4/7 SNAT mode requires no mode-specific configuration changes to the servers and it can be deployed using either a one-arm or two-arm configuration:

You should not use the same RIP:PORT combination for layer 4/7 SNAT mode VIPs because the required firewall rules conflict.

Layer 4/7 SNAT mode supports port translation and it is not transparent.

If transparency required, layer 7 SNAT mode can be configured to provide client IP address to the servers in two ways:

- By inserting a header that contains the client’s source IP address.

- By modifying the source address field of the IP packets and replacing the IP address of the load balancer with the IP address of the client.

Load balancing algorithms

Finally, let’s look at the load balancing algorithms, a set of implemented rules at different layers of the OSI model that a load balancer follows to determine for each of the different client requests the best server in a pool in order to keeping the distribution even and efficient. Load balancing algorithms fall into two main categories:

Static load balancing algorithms

Static load balancing follows fixed rules and are independent of the current server state, sending an equal amount of traffic to each server in a pool, either in a specified order or at random. Some recommendations on when to use static load balancing algorithms are:

- You have a low or stable fluctuation in incoming traffic and do not need to adjust to changing network conditions.

- You want to simplify the configuration and maintenance of your servers and load balancer.

- You have servers with similar capacities and resources and want to distribute traffic evenly among them.

- You are concerned about the resource consumption and latency of your load balancer and servers.

Let’s see some examples of static load balancing algorithms:

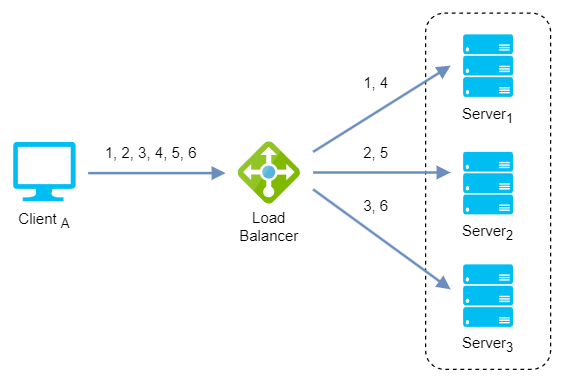

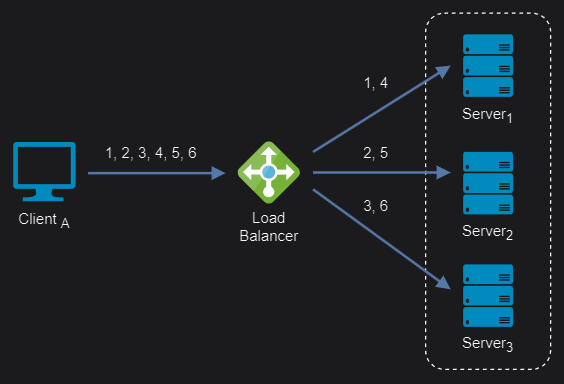

Round-robin: It is a simple way to distribute client requests among a group of servers. A request from a client is sent to each server in turn. The algorithm instructs the load balancer to go back to the top of the list and repeat the process. It is easy to implement and the most widely deployed load balancing algorithm, working best when servers have roughly identical computing capacities.

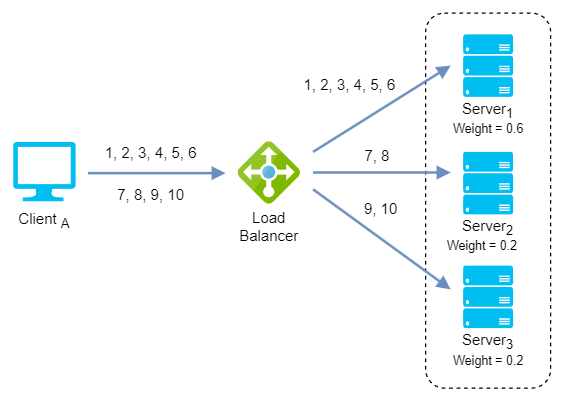

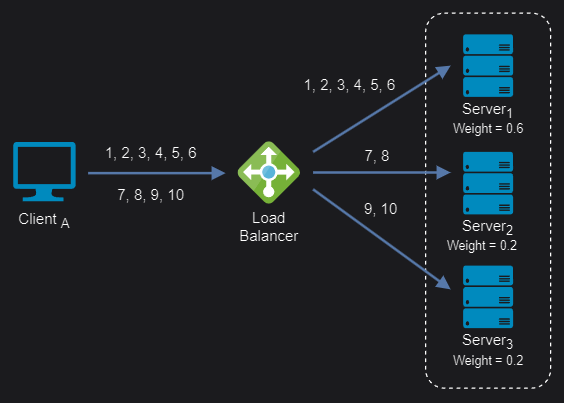

Weighted round-robin: It is an improvement over the above round robin algorithm which may result in uneven distribution of traffic. It distributes client requests based on the individual capacities or weights of the servers. A server with a higher weight will receive more requests than a server with a lower weight. The algorithm cycles through the servers and assigns a fixed number of requests to each server according to its weight.

Weighted round-robin algorithm

Weighted round-robin algorithm

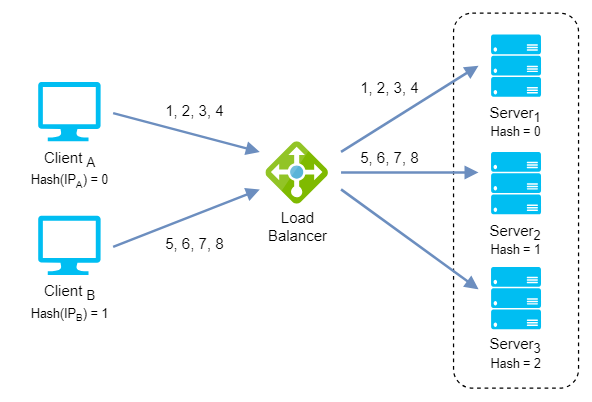

IP Hash: It is based on the source and destination IP addresses of each packet. It uses a mathematical calculation to generate a hash value that determines which server to send the packet to. This way, packets from the same source and destination IP addresses are always sent to the same server, ensuring session persistence and optimal performance.

Dynamic load balancing algorithms

Dynamic load balancing uses algorithms that take into account the current availability, workload, and health of each server and distribute traffic accordingly. Some recommendations on when to use dynamic load balancing algorithms are:

- You have a high fluctuation in incoming traffic and need to adapt to changing network conditions.

- You want to avoid overloading or failing any server and ensure optimal performance and availability for your application.

- You have servers with different capacities and resources and want to distribute traffic accordingly.

- You are willing to invest in more complex configuration and monitoring of your servers and load balancer.

Let’s see some examples of dynamic load balancing algorithms:

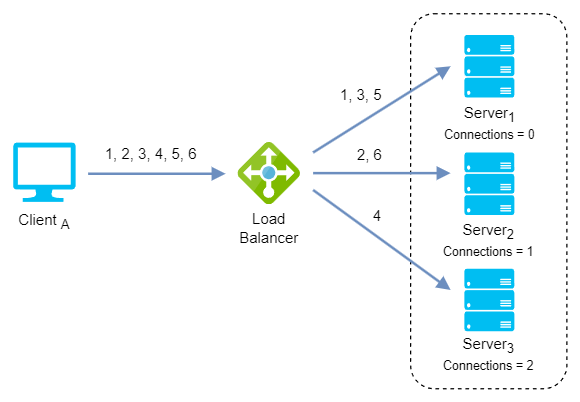

Least connection: It checks which servers have the fewest connections open at the time and sends traffic to those servers. This assumes all connections require roughly equal processing power.

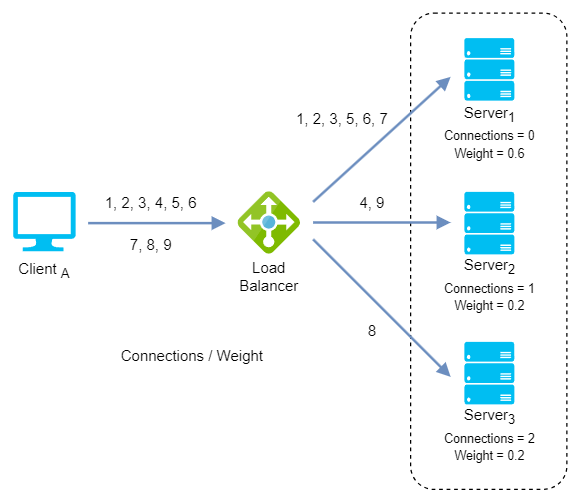

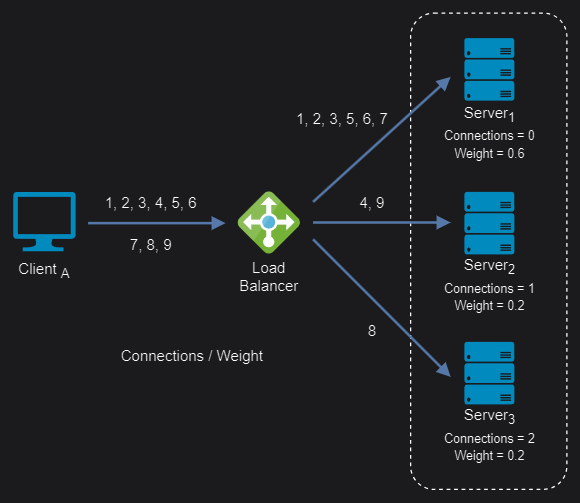

Weighted least connection: It assigns different weights to each server, assuming that some servers can handle more connections than others. Incoming requests are distributed to the servers with the lowest response time relative to their weight.

Weighted least connection algorithm

Weighted least connection algorithm

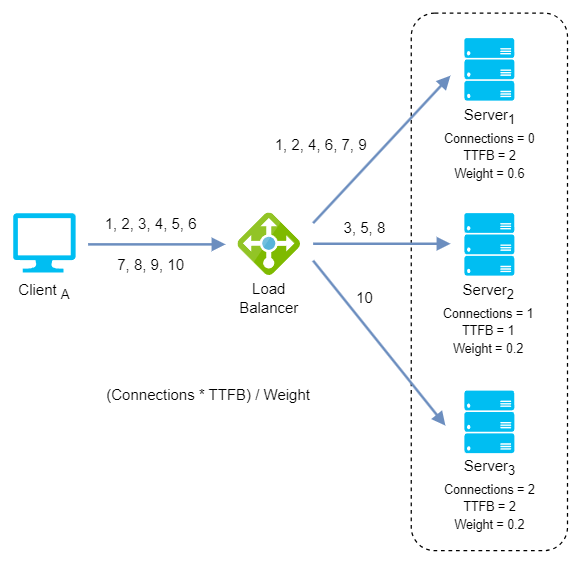

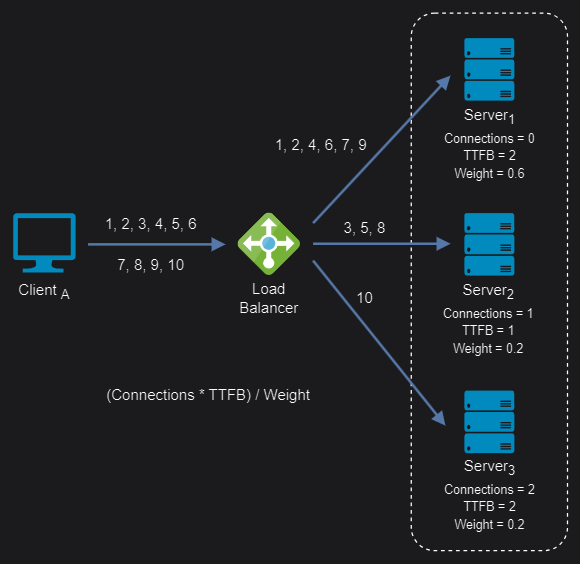

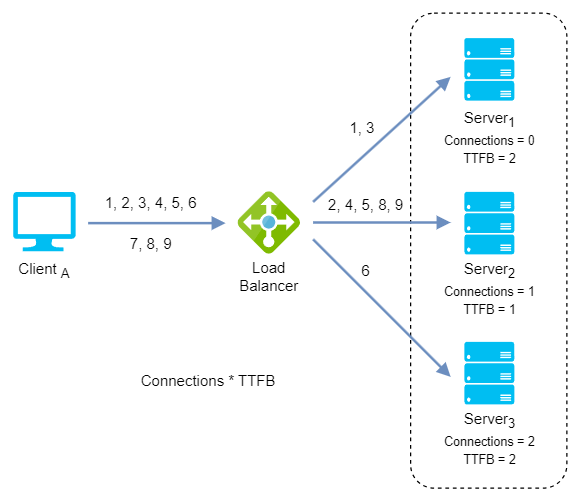

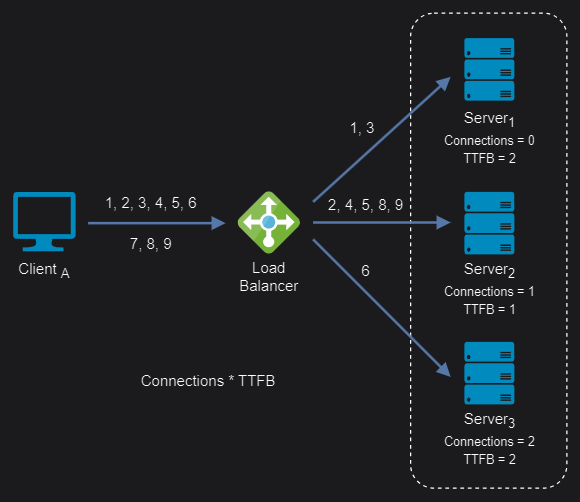

Least response time: It distributes network traffic among the servers based on the number of active connections and the average response time of each server (time to first byte or TTFB). This assumes that servers with lower response times are less busy and can handle new requests faster.

Weighted least response time: Again, different weights are assigned to each server. Incoming requests are distributed to the server with the lowest ratio of weight and active connections, and response time values.

Weighted least response time algorithm

Weighted least response time algorithm

Summary

I have tried to collect here a reference with the key concepts we should be familiar with in order to deal with an infrastructure where they come into play, but the field of load balancers and reverse proxies is broader and could be complicated enough to be a subject of its own study. In future posts I will try to show the implementation of some current solution in the market to solve some example scenario.

Comments powered by Disqus.